Species Diversity

Over the past ten years, we’ve been monitoring and evaluating how water for the environment supports the diverse species in the Murray Darling Basin. Here, we share the key insights and lessons learned to inform future water management and ecological planning.

Image: Southern bell frog at a Commonwealth environmental watering site in the Lower Murrumbidgee.

Photo credit: Anna Turner

Introduction

The Murray-Darling Basin is a freshwater biodiversity hotpot in Australia. It is a rich tapestry of water-dependent ecosystems and habitats that includes rivers, streams, billabongs, lakes, wetlands, floodplains and an estuary. The Basin provides critical habitat and resources for a wide range of native species, including waterbirds, frogs, reptiles, mammals, and woodland dependent birds.

The Species Diversity theme estimates how Commonwealth environmental water contributes to protecting and recovering species populations across the Basin.

Note: The contents on this page includes summarised text from the following report: 2023-24 Basin-scale evaluation of Commonwealth environmental water: Species Diversity. Page number references have been noted throughout the content below for anyone using the full report.

Definitions

The Australian National Aquatic Ecosystem Classification (ANAE) is a systematic framework that categorises aquatic ecosystems in Australia, focusing on their ecological characteristics, functions, and values. It aids in biodiversity conservation, environmental water management, and policy development by providing a standardised approach to understanding aquatic habitats.

The managed floodplain is the estimated area of the Basin that can be influenced-by or associated with environmental water management. It includes actively managed areas that can receive environmental water delivered from large headwater storages, or via ‘environmental works’ sites on the Murray River floodplain from The Living Murray Program. It also includes passively managed areas that receive environmental water via flow rules in water resource plans, or via natural events.

The variety and abundance of species with the Murray-Darling Basin system which is measured as species richness. We measured species richness by counting the number of species present within a set area and measured using gridded maps.

International agreements to protect migratory bird species shared between Australia and other countries, including China, Japan and Korea.

Our approach

The species diversity evaluation addresses the following overarching question:

What did Commonwealth environmental water contribute to species diversity?

This question is addressed through three main components:

What was the contribution of Commonwealth environmental water to the diversity of frogs, waterbirds and other water-dependent vertebrates?

What was the contribution of Commonwealth environmental water to listed species and ecological communities?

What was the contribution of Commonwealth environmental water to migratory species listed under international agreements (Bonn Convention, CAMBA, JAMBA or ROKAMBA).

The evaluation combines both on-ground monitoring and the use of multiple datasets to further our understanding of the role of Commonwealth environmental water in conserving our species. The evaluation draws on these three key sources of information.

Selected area data collected throughout the Long-Term Intervention Monitoring Project (2014-19) and Flow-MER (2019-24).

Complementary waterbird survey data collected by the NSW Department of Climate Change, energy, the Environment and Water.

Data from the Atlas if Living Australia to collate Basin-wide patterns of listed and migratory species.

Our ability to adequately address species diversity outcomes is limited by the lack of available data that capture responses to the delivery of Commonwealth environmental water across the Murray-Darling Basin (pg. iv).

Machine-Learning Algorithms

In 2022–23, the Flow-MER Species Diversity Report trialled the use of machine-learning algorithms to explore links between Commonwealth Environmental Water (CEW) and outcomes for threatened species. This approach provided a valuable reporting framework, which has been further developed and expanded in the 2023–24 evaluation year.

The machine-learning algorithm is a computer-based model designed to identify patterns and relationships between environmental water deliveries, site characteristics, and recorded occurrences of species. The analysis focused on five threatened bird species:

- Australian Painted Snipe

- Common Greenshank

- Sharp-tailed Sandpiper

- Latham’s Snipe

- Superb Parrot

Using data collected over the 10-year program period (2014–2024), the algorithm assessed which environmental and spatial features were most influential for each species and evaluated the model’s ability to predict their presence (pg. 62).

For the full results, see page 62 of the report.

Contribution to the Basin Plan

Our work assesses outcomes for frogs, waterbirds, migratory species, species listed under the Environmental Protections and Biodiversity Conservation Act (EPBC) and other water-dependent vertebrates, such as reptiles (including turtles), mammals and woodland birds (page iii). This evaluation examines the contribution of Commonwealth environmental water to the Basin Plan objectives outlined in Section 8.05 (pg. 3).

Section 8.05: ‘to protect and restore biodiversity that is dependent on Basin water resources by ensuring that’

Find a detailed breakdown of section 8.05, refer to the full report- (link to report)

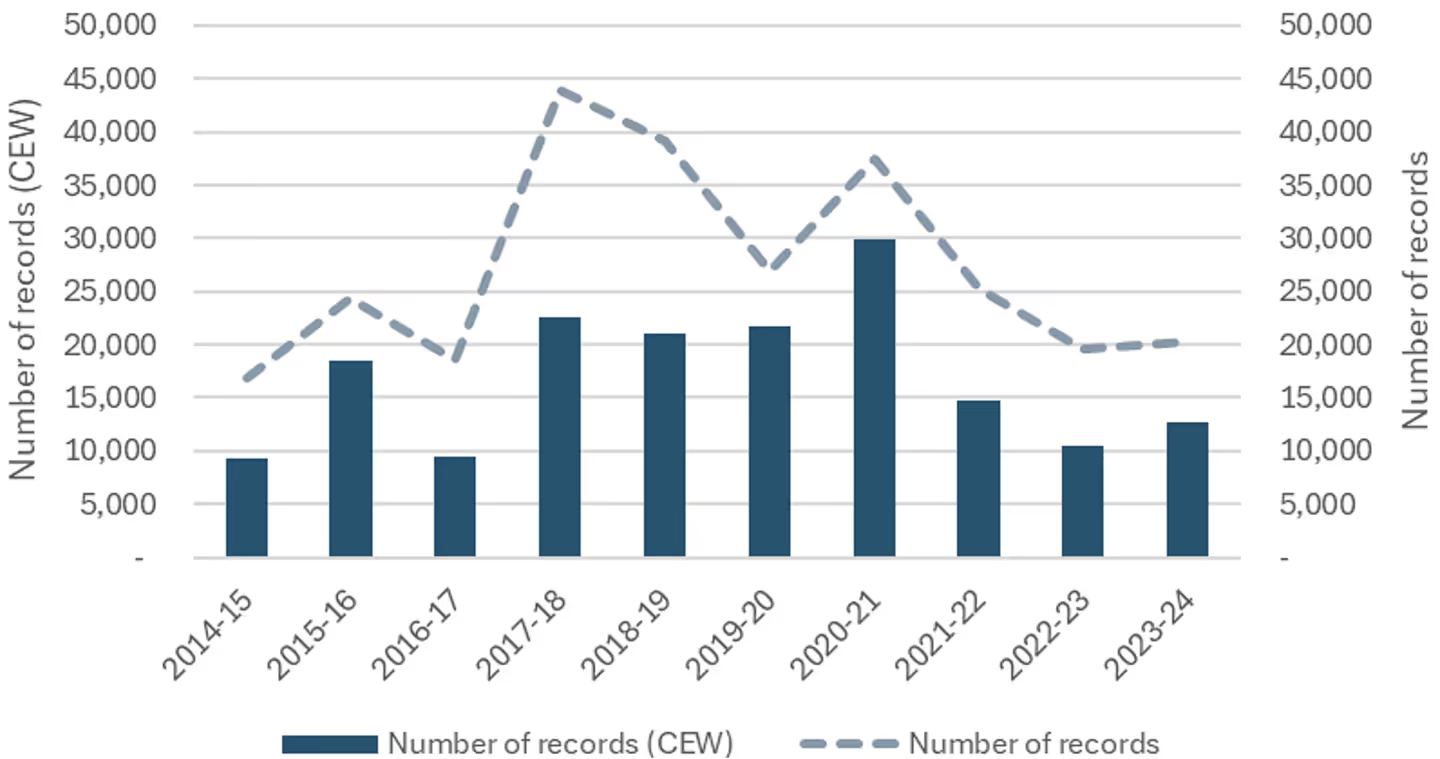

Commonwealth environmental water delivery

In 2023–24,75 watering actions were undertaken with objectives for species diversity (waterbirds, frogs, listed threatened and migratory species or other biota), delivering 2,324 GL of Commonwealth environmental water (pg. 7).

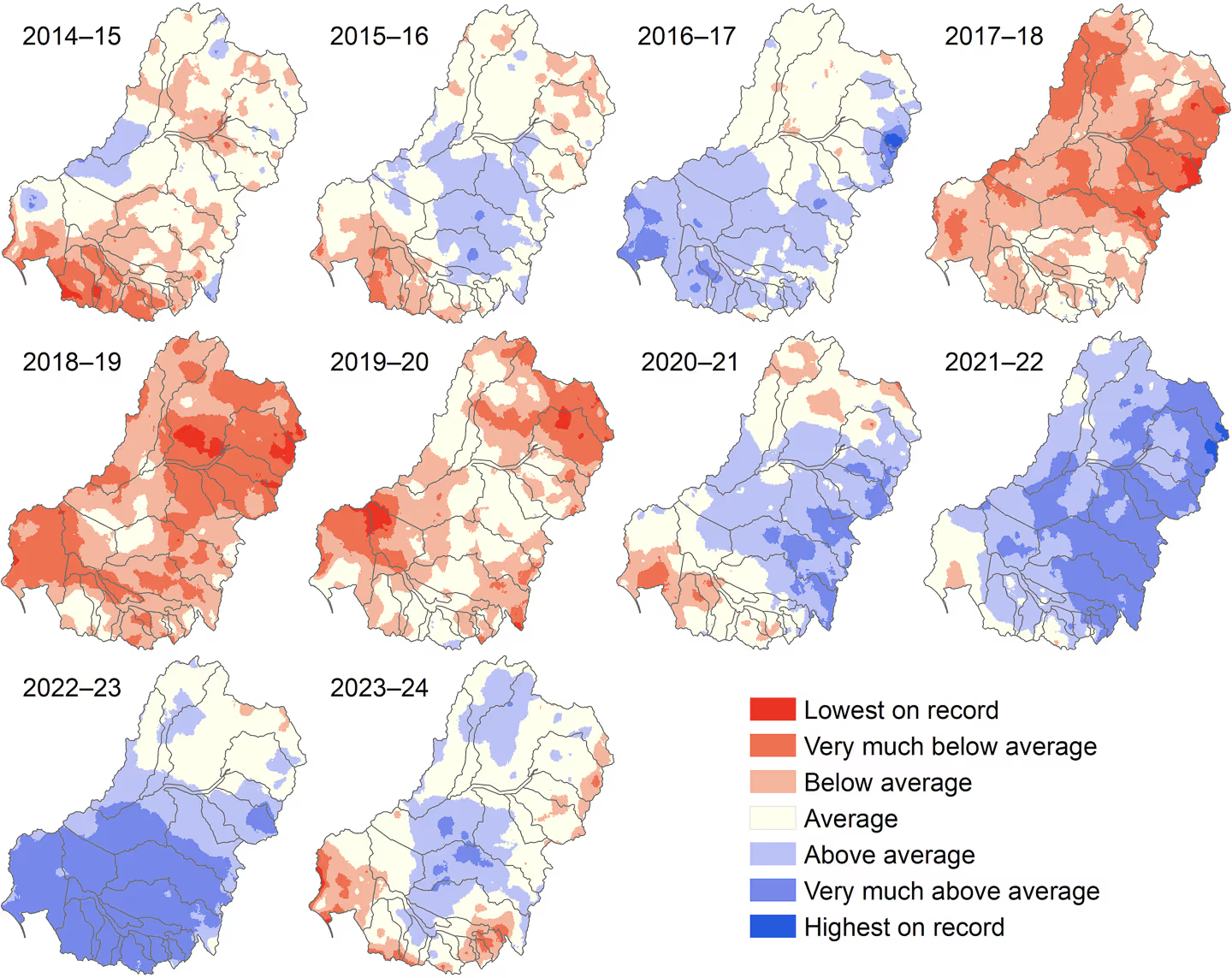

Rainfall

While the overall rainfall in Australia during 2023–24 was above the average, the Basin experienced a slight departure from the mean (−3%). Average rainfall was 479.9 mm (pg. 7).

- The southern and northern parts of the Basin received average rainfall

- Large parts of central New South Wales and central Victoria experienced above-average or very much above-average rainfall.

- Parts of the Basin in South Australia, the upper Murray catchment, and smaller areas on the north-eastern New South Wales, experienced below-average rainfall (Figure3.1)

Evaluation

Frogs

We evaluate how Commonwealth environmental water contributed to maintaining, improving or restoring habitat for native frogs in the Basin (pg. 11). Please note that this data is at a site or System scale, not a Basin scale due to limited long-term monitoring data.

Globally, amphibians have the highest percentage of species at risk of extinction (Luedtke et al. 2023). In Australia, 22% of species are listed under the EPBC Act, and 4 frog species are known to have become extinct in the past 40 years (Geyle et al. 2021).

Watering Actions (2023-24)

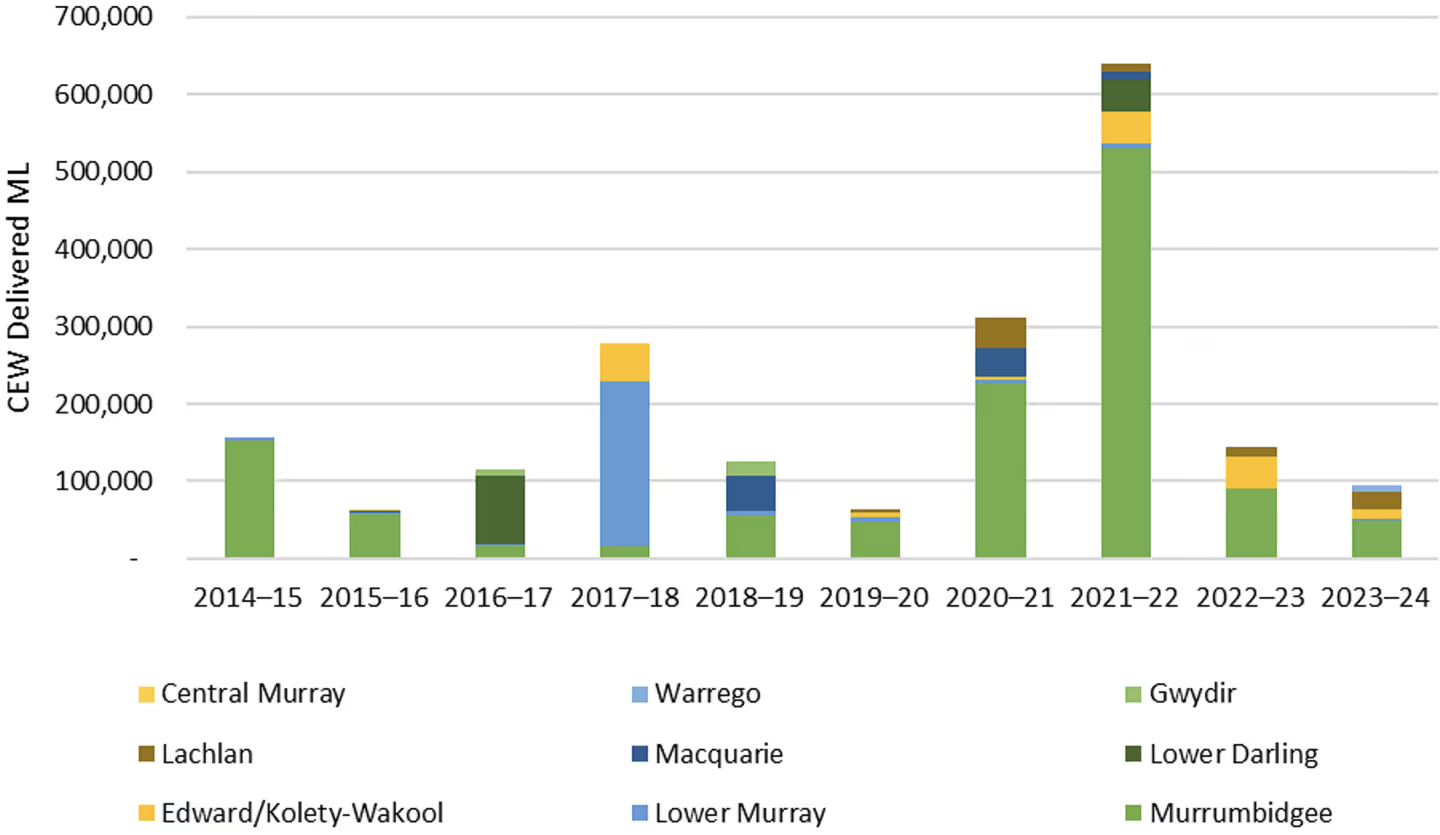

In 2023–24, about 94,650 ML of commonwealth environmental water was delivered over 25 individual watering actions that had at least one objective related to frog outcomes. Most of the water was delivered with outcomes relating to habitat support for multiple taxonomic groups.

Of these actions, water deliveries with specific objectives for the southern bell frog were undertaken in the Murrumbidgee (4 actions, 49,675 ML) and Lower Murray (7 actions, 1,773ML).

Key Findings (2023-24)

- In 2023–24, 11 species of frog were detected.

- The most abundant and widespread were the spotted marsh frog, barking marsh frog, and Peron’s tree frog, which were detected in both the junction of the Warrego and Darling rivers in the northern Basin and the Murrumbidgee River System in the southern Basin.

- As in previous years, the diversity of frog species is higher in the northern Basin due to the presence of species that respond to rain. In the Murrumbidgee River System, the Vulnerable (EPBC Act) southern bell frog continues to benefit from the delivery of environmental water (pg. 13).

Watering Actions (2014-24)

Over the past 10 years 1,991GL of CEW was delivered with specific objectives for frogs. When broken down by valley, the highest volumes of water with objectives for frogs over 10 years were delivered in the Murrumbidgee, followed by the Lower Murray, Edward/Kolety–Wakool, Lower Darling/Baaka, Macquarie, Lachlan, Gwydir and Central Murray river systems (pg. 12).

Key Findings (2014-24)

- Over the 2014–24 period, 20 species of frog were reported from wetlands inundated with Commonwealth environmental water in the Murrumbidgee River System, Junction of Warrego and Darling rivers, Macquarie Marshes, Lachlan River System and Gwydir River System

- Commonwealth environmental water was the primary source of inundation and played a significant role in shaping the hydrological regime at 11 of the 12 frog survey sites in the Murrumbidgee River System

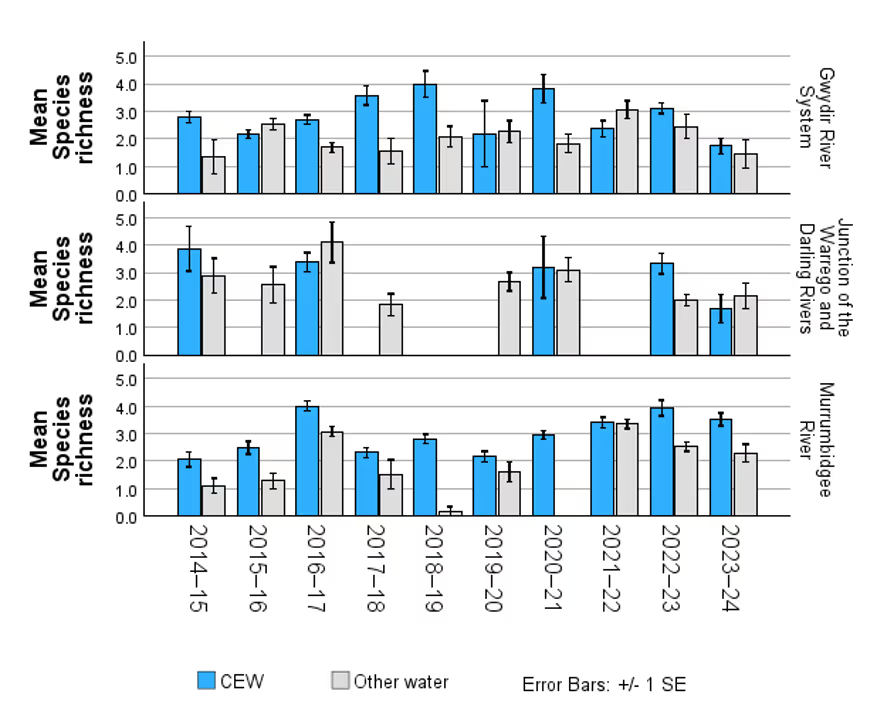

- Overall, there is little difference between the mean numbers of species recorded in a given water year and the source of water and few trends are detected. However, increasing the frequency of inundation of CEW makes a contribution to the persistence of sensitive species including the southern bell frog which has low survival during dry periods

Waterbirds

Populations of many Australian waterbirds are declining (Porter et al. 2021). These declines and the high proportion of listed species make waterbirds a key priority for environmental watering, particularly in floodplain and wetland habitats.

There is growing evidence of the importance of environmental water in maintaining waterbird populations in Australia, especially at the catchment scale (MDBA, 2017). Critical waterbird habitats and multiple populations of listed waterbird species are associated with locations periodically inundated by environmental water (pg. 23).

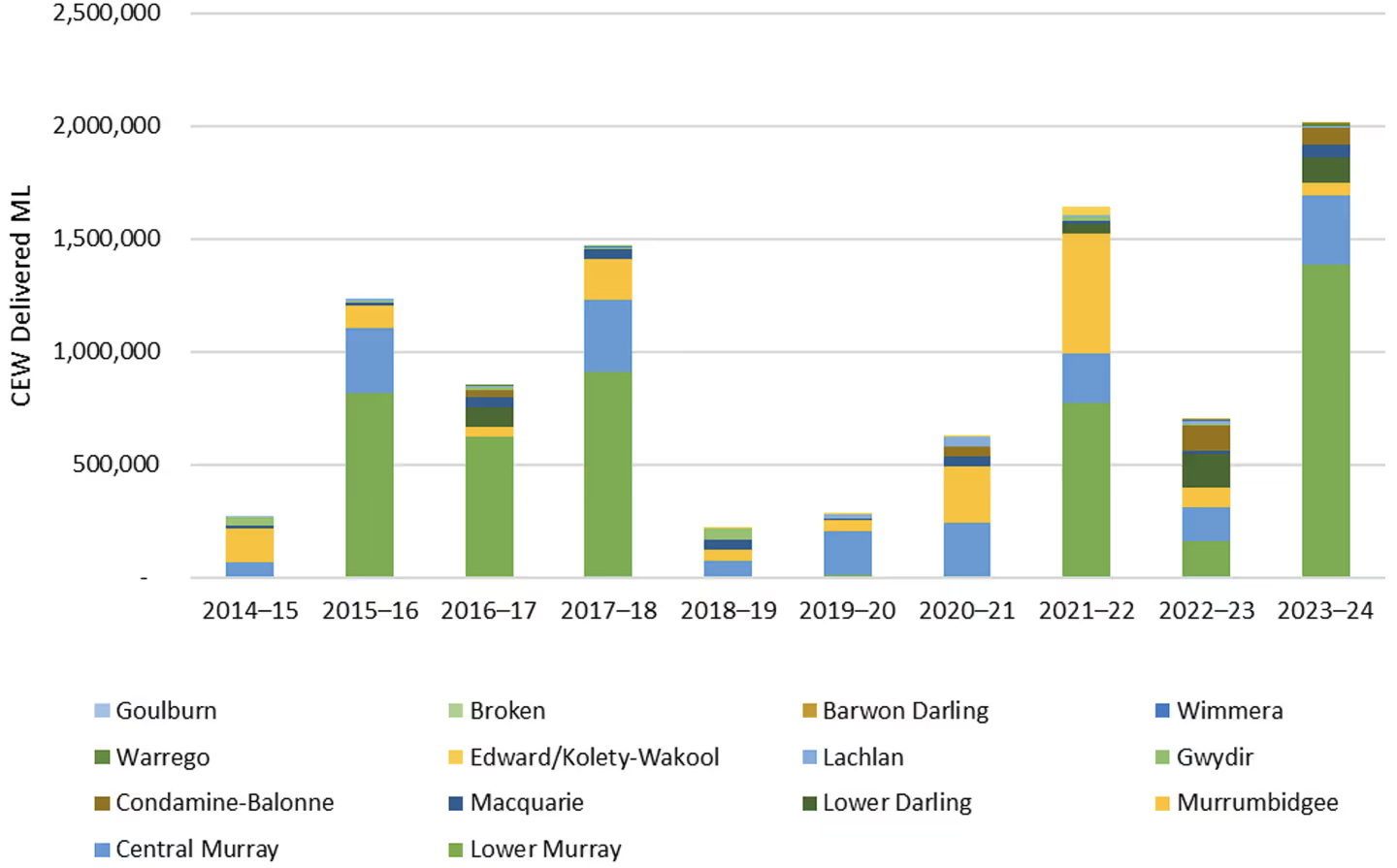

Watering Actions (2023-24)

In 2023–24, 36 individual watering actions had at least one objective related to waterbird outcomes, for a combined volume of approximately 2,011,400 ML of CEW. Most CEW was delivered with objectives related to habitat support and included outcomes for multiple taxonomic groups. Flows with specific objectives related to listed threatened and migratory species were undertaken in the Murrumbidgee (Australasian bittern and Australian painted snipe) and Lower Murray (migratory shorebirds). The overall volume of CEW delivered with at least one objective for waterbirds in 2023–24 was 2,011,400ML, the highest on record (pg. 24)

Key findings

- 68,718 individuals from 68 species were reported from 8 waterbird functional groups and 2 water-associated groups (reed-inhabiting passerines and raptors).

- Grey teal (Anas gracilis) was the most recorded species, followed by Australian pelican (Pelecanus conspicillatus), Eurasian coot (Fulica atra), Pacific black duck (Anas superciliosa) and Australian wood duck (Chenonetta jubata).

- 11 bird species of conservation significance were detected during the combined NSW DCCEEW and Flow MER waterbird surveys. These included 3 species listed under the EPBC Act–the Endangered Australasian bittern and Vulnerable sharp-tailed sandpiper and Latham’s snipe.

- The number of waterbirds reported from Narran Lakes in NSW DCCEEW surveys was low compared to previous years, likely due to a combination of drier conditions and low survey effort (pg. 26)

Breeding

A total of 86,076 ML across 5 actions of CEW was delivered with objectives related to waterbird breeding across the following valleys:

- Condamine Balonne- 71,299 ML

- Warrego- 8,369 ML

- Lachlan- 3,646 ML

- Wimmera- 2,762 ML

Surveys carried out in November by UNSW on behalf of NSW DCCEEW identified approximately 1,000 pelicans foraging, and repeated drone surveys provided a total nest count of estimate of approximately 20,000 (Francis and Brandis 2024) (pg. 30).

Watering Actions (2014-24)

Over the 10 years (2014-24), 9,298,500 ML of CEW was delivered to benefit waterbirds, either alone or in combination with other watering objectives. The volumes of CEW delivered with watering objectives related to water birds were highly variable across years (pg. 24).

Key findings (pg. 26)

- Over the past 10 years, 224,921 individuals from 97 waterbird species were detected from the Junction of Warrego and Darling rivers, the Gwydir River System and the Murrumbidgee River System

- By directly influencing the proportion of wetted area, CEW contributed to supporting an additional 13,951 individuals and an additional 3 species over what would be expected with other water sources alone, for a total of 100,921 individuals from 93species

- Notable species detected during surveys when sites were associated with CEW include the listed migratory charadriiform shorebirds common sandpiper (Actitis hypoleucos), sharp-tailed sandpiper (Vulnerable, EPBC Act), red-necked stint (Calidris ruficollis),long-toed stint (Calidris subminuta), little curlew (Numenius minutus), wood sandpiper (Tringa glareola),common greenshank (Endangered, EPBC Act) and marsh sandpiper, along with the EPBC Act-listed Australian painted snipe, Latham's snipe and Australasian bittern

Breeding

Of the 32 monitored sites in the Murrumbidgee, only 2 (Euroley Lagoon and Narrandera Regional Park Lagoon) were never associated with Commonwealth environmental water. Commonwealth environmental water was the primary source of inundation and a major driver of the hydrological regime at other sites, including Piggery Lake, Yarradda Lagoon, Two Bridges Swamp and Telephone (Bayil) Creek in the Murrumbidgee and Combardello Wier, Bunnor Bird Hide in the Gwydir. Hydrological regime and Commonwealth environmental water contributions were more variable in the Junction of Warrego and Darling rivers with only one site (Boera Dam) associated with Commonwealth environmental water across more than 5 years.

When considered across the Gwydir and Murrumbidgee valleys, the contribution of Commonwealth environmental water was particularly important in drier years (2017–18 to 2020–21), when it was the primary source of inundation at the waterbird monitoring sites (pg. 30).

Species richness (pg. 35)

- Species richness was significantly higher when sites were inundated with CEW compared to years when no CEW was delivered.

- Commonwealth environmental water contributed the most to species richness in drier years (2014–16, 2017–20), when it was the primary source of floodplain inundation.

- The relative contributions of CEW and other water sources to species richness were similar during the very wet years in 2016–17 and 2021–23, when there was broad-scale unregulated floodplain inundation

Listed threatened and migratory species

We identified water-dependent species that are listed under relevant Commonwealth or state legislation or international treaties and that occur on the managed floodplain: 65 birds,6 frogs,11 fish,6 crustaceans,2 mammals and 9 reptiles. Of these, we identified 62 waterbirds and raptors, 5 frogs, 11 fish, one crustacean, 2 mammals, 2 water-associated woodland birds and 7 reptiles with at least one record coinciding with habitats associated with CEW (pg. 38).

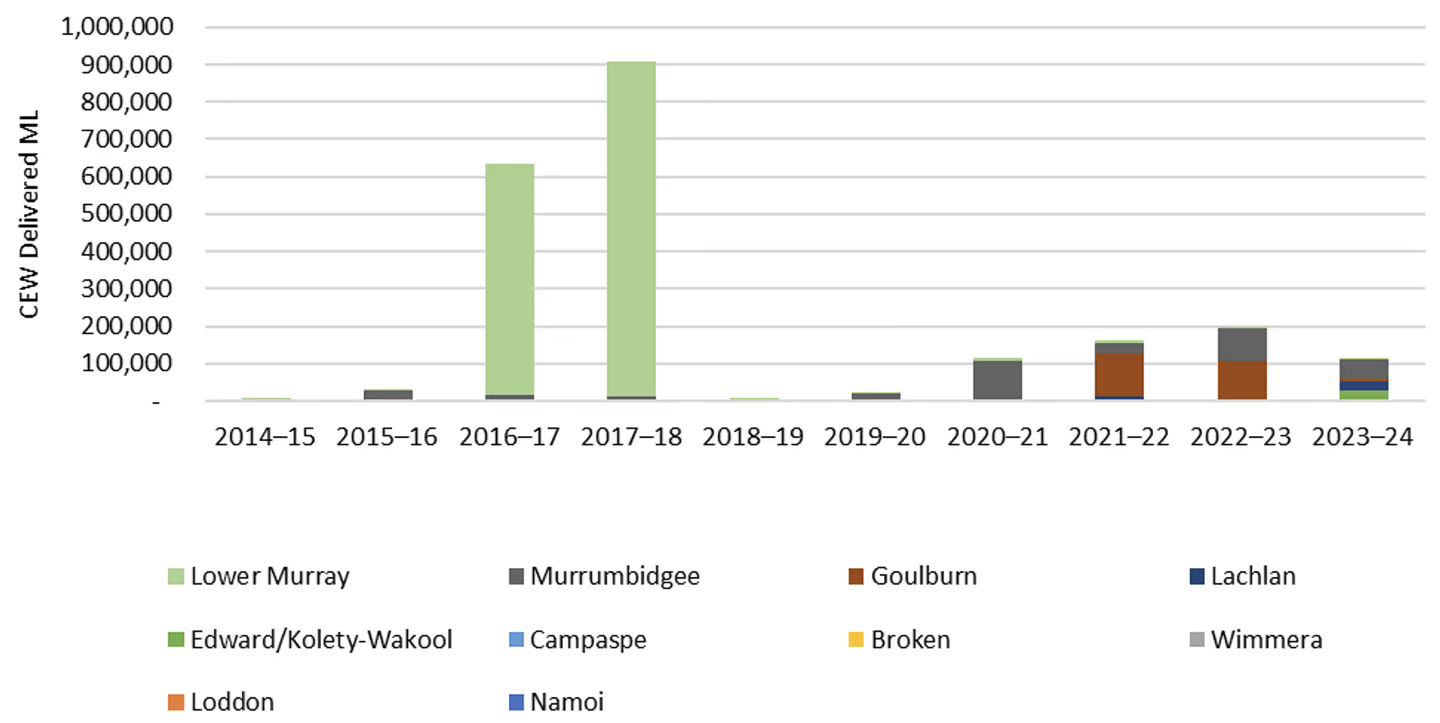

Watering Actions (2023-24)

In 2023–24, 14 individual watering actions had at least one watering objective related to listed species, for a combined volume of 74,473 ML of CEW (pg. 39).

Most of the water was delivered with objectives for multiple taxonomic groups and included specific mention of a listed species. In the Murrumbidgee, water was delivered with specific objectives for multiple threatened species, including Australasian bittern, southern bell frog, southern myotis (Myotismacropus), southern pygmy perch (Nannoperca australis), Murray cod (Maccullochella peelii), trout cod (Maccullochella macquariensis), freshwater catfish (Tandanus tandanus) and silver perch (Bidyanus bidyanus).

Commonwealth environmental water actions in the Lower Murray focused on migratory shorebirds, regent parrot (Polytelis anthopeplus), Murray hardyhead (Craterocephalus fluviatilis) and southern bell frog. Southern bell frogs and platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) were the focus of watering actions in the Edward/Kolety–Wakool, platypus in the Goulburn and Namoi, and southern bell frogs in the Lachlan.

Smaller actions were undertaken in the Goulburn, Lower Murray and Namoi valleys.

Key findings (pg. 42)

Across the managed floodplain, CEW was associated with 7 EPBC Act-listed water-associated bird species:

- Australasian bittern

- Curlew sandpiper (Calidris ferruginea)

- Sharp-tailed sandpiper

- Eastern curlew (Numenius madagascariensis)

- Latham's snipe

- Australian painted snipe

- Common greenshank

Another 12 EPBC Act-listed species were observed including;

- Southern bell frog

- Grey snake (Hemiaspis damelii)

- Murray cray (Eustacus armatus)

- Superb parrot (a woodland bird species).

- Macquarie perch (Macquaria australasica)

- Murray cod

- Silver perch

- Trout cod

Watering Actions (2014-24)

Over the 10 years (2014-24), 2,201 GL of CEW was delivered to benefit listed birds, frogs, mammals and reptiles, either alone or in combination with watering objectives. The volumes of CEW delivered with watering objectives related to listed species were highly variable across years.

Two very large actions undertaken in the Lower Murray with objectives for migratory waterbirds in the Northern Lagoon of the Coorong and Lower Lakes occurred in 2016–17 and 2017–18. These comprised 618,476 ML with the objective to ‘Protect water quality in the Northern Lagoon for benthic invertebrates; a key food source for migratory birds’ and 681,127 ML delivered with the objective to ‘Protect habitat conditions to maintain benthic invertebrate food resources for annual migratory waders within the Coorong’. Since that time, most actions have been undertaken in the Murrumbidgee.

Key Findings

Listed and threatened migratory waterbirds species

- Between 2014–15 and 2023–24, 59 listed threatened or migratory waterbird and raptor species were reported from habitats that received Commonwealth environmental water on at least one occasion over the 10-year period.

- There were 26 listed water- dependent crustaceans, fish, frogs, reptiles and mammals reported from habitats that received Commonwealth environmental water on at least one occasion over the10-year period.

- Overall, the number of listed threatened and migratory waterbird species observed in the Basin has remained relatively stable, ranging from a low of 39 in 2023–24 to a high of 48 in 2017–18. However, there is a concerning trend towards fewer records of listed threatened and migratory species since the peak in 2020–21.

Other listed and threatened species

- the overall numbers of listed threatened species have remained relatively stable over the past 10 years, ranging from a low of 17 in 2015–16 to a high of 23 in 2021–22

Informing Adaptive Management

The monitoring and evaluation of outcomes remain significantly lacking for frogs, listed threatened and migratory species, and other biota. Analysis of available data from the LTIM and Flow-MER programs demonstrated positive associations between waterbird and frog species richness and the area of habitat inundated during surveys.

Additionally, CEW was identified as the main contributor to inundation at most monitored sites, playing a critical role in driving habitat availability and influencing waterbird and frog diversity patterns, particularly during drier years. There were multiple instances where CEW was delivered with objectives aimed at supporting species diversity or listed threatened and migratory species.

However, these actions were accompanied by no, or very limited, evaluation of success, constraining their ability to inform adaptive management. In most instances, listed threatened and migratory species are reported from habitats that were associated with CEW without any specific objectives, and it remains unclear whether these actions had a positive, neutral or negative impact on habitat suitability (pg. 73).

Improving our approach

In most cases, monitoring approaches do not meet minimum survey requirements for listed species. Greater consideration of known or potential habitats that support listed species as part of water planning, along with investment in robust monitoring capable of detecting target species, is critical to ensure that desired outcomes are achieved (pg. 73).

Detection-only datasets, including ALA and NSW DCCEEW data provided through the BioNet platform, create challenges when modelling the relationship with CEW. Where targeted surveys for threatened species are undertaken, they often focus exclusively on areas that receive CEW, and there is limited monitoring of other habitats which could act as a control or long-term monitoring of the same areas in years when no CEW is delivered (pg. 73).

Despite containing the highest proportion of the Basin’s biodiversity and listed species, basic hydrological information for floodplains and wetlands is limited. Reliance on annual timesteps for inundation mapping makes it difficult to align species occurrences with CEW management (pg. 73).

With the notable exceptions of southern bell frog and Australasian bittern, there remains a disconnect between conservation strategies listed in species recovery plans, long-term water plans and CEWH watering objectives. One way to improve objective setting for listed threatened and migratory species is to foster and support collaboration between water managers, threatened species managers and species experts and to explicitly consider conservation strategies outlined in species recovery plans when setting watering objectives (pg. 73).

Contribution to Basin Plans Objectives

Commonwealth environmental water has made substantial contributions to achieving the objectives and desired outcomes of the Basin Plan and the Strategy. In most cases, Commonwealth environmental water is shown to have supported outcomes (that is, in conjunction with other water delivery) or contribution is inferred from recorded observations at monitoring locations receiving environmental water.

Knowledge Catalogue

News

.webp)

A collection of threatened and migratory species of the Murrumbidgee Valley

A range of threatened species make their home in and around the Murrumbidgee. These include brolgas, Australasian bitterns, southern bell frogs, and many other species. Knowing where these animals live is important. This information guides decisions about where and when to use wa

Artificial intelligence helping protect threatened species

Researchers are using AI to predict habitat conditions for threatened species like frogs and waterbirds, helping guide environmental water management. Learn how data-driven models improve decision-making for protecting the southern bell frog.